Speech-Language Pathology: An Overview

The field of speech-language pathology includes the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of communication disorders and differences as well as feeding and swallowing.

There are nine main areas of focus, which are often referred to as the “Big 9.” They include:

- Articulation

- Voice and Resonance

- Fluency

- Receptive and Expressive Language

- Social Aspects of Communication

- Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

- Cognition

- Aural Rehabilitation

- Swallowing and Feeding

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) may work with individuals across the lifespan in a variety of settings, including (but not limited to) the individuals’ homes, hospitals, clinics, and schools.

Evidence-Based Practice: An Overview

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is not unique to the field of speech-language pathology. It was originally developed for medicine but is now used across many disciplines, including social work, occupational therapy, nursing, and public health.

The purpose of evidence-based practice is to enhance informed decisions related to patient care.

Broadly speaking, it is a practice of combining client perspectives, clinical expertise, and evidence.

In the field of speech-language pathology, EBP may look like this:

Imagine you are working in an outpatient clinic and have a new client who recently had a stroke. You complete an assessment and determine they have nonfluent aphasia. While determining your next steps in treatment, you may consider these three areas:

1) Client Perspectives: What does the client hope to achieve during treatment?

- Example: The client wants to be able to have phone calls with her adult children.

2) Clinical Expertise: What do you know about the client’s condition?

- Example: You have worked with clients with aphasia who have benefitted from script training to have short conversations, like phone calls.

3) Evidence: What does the evidence say about this treatment approach?

There are two types of evidence to consider: internal and external.

- Internal evidence: data you’ve collected from your client.

- Though you haven’t worked with your client for a long time, you have seen them find success speaking verbally when phrases are written down for them to read.

- External evidence: data from scientific literature.

- Script training for people with aphasia to increase and improve spoken utterances has been researched extensively and shows clinically significant progress.

You conclude that a treatment approach that includes script training, with scripts related to phone calls, would be beneficial for your client.

As you can see, using EBP can increase both client buy-in to your services AND the effectiveness of treatment.

The Role of Research in Speech-Language Pathology

Research is one part of evidence-based practice and includes both external evidence and internal evidence.

External Evidence

External evidence includes scientific literature, such as peer-reviewed research articles. In graduate school, future SLPs learn a lot about research-backed assessment and treatment approaches. Some graduate students may even actively complete research under professors who are experts in their field.

Research may provide information about various clinical areas of focus. Some examples include:

- The effect of dietary changes in people with dysphagia

- The use of minimal pairs in treating speech sound disorders

- How individuals who use AAC develop communication skills

- Training programs for teaching vocabulary to individuals with developmental language disorders

Being aware of research-backed approaches is important for effective treatment. For example, if you begin working with a new client with complex communication needs who is going to use an AAC device, you can look into scientific literature that researched how individuals who use AAC develop communication skills. This can help you make decisions about grid size, vocabulary to include, and methods for teaching communication.

However, just looking at the research is not enough. Why not? There are many limitations to research. Limitations may include:

- Research that doesn’t reflect your client’s profile (e.g., the population studied was monolingual clients aged 6-8, and your client is 4-years-old and exposed to two languages)

- The clients received services three times a week, and your client is only available one time a week

- The treatment took place in a clinic setting, while you are seeing your client in their home.

Internal Evidence

Internal evidence includes collecting and analyzing subjective and objective information about the client you’re working with. This comes into play after you’ve been working with a client for some time. For example, if you are developing a new treatment plan for a client (e.g., a new IEP in the schools or a new plan of care), you can consider how your client has responded to your current treatment approaches.

For example, if you’re working with a younger child, you might ask yourself: Have they demonstrated good progress and participation when you had play-based sessions where they chose what to play with? Has more progress and participation been observed when you have more structured sessions? Have they benefited from shorter sessions that occur more frequently, or do they need more time to transition into sessions and seem to benefit from longer sessions that occur less frequently?

Reflecting on the client’s progress and participation over a period of time is an important part of refining and updating treatment plans.

It can be challenging to find strong research studies (i.e., external evidence) that fully reflect your client’s experience. As we all know, the human profile can look so different! Additionally, if you are working with a new client, or are going to target a new goal with an existing client, internal evidence may not be enough.

That leads us to the other aspects of EBP…

The Role of Clinical Expertise in Speech-Language Pathology

Clinical expertise is an intricate part of EBP. This means SLPs use their background and experience to make decisions about assessment and treatment.

For example, an SLP may have worked in a preschool setting for a few years. They have completed over 50 evaluations for preschool-aged children with suspected speech and language delays. They may know what informal assessment measures tend to provide the most information in the shortest amount of time, which is important for young children with limited attention spans. The SLP may have consistent, positive outcomes when they bring in a specific toy or engage in a particular activity, which they know can help elicit a comprehensive speech and language sample.

However, just using clinical expertise (and evidence) is not enough. Why not? There are still limitations. Limitations may include:

- No matter how long you have been in the field, you haven’t encountered all clients and all situations. You are bound to work with a new client whose background is different from what you’ve seen before.

- Additionally, the client may have different preferences or perspectives from yours. It is important to be culturally-responsive and honor any cultural and linguistic differences of your clients.

- In addition to EBP, this is also an essential ethical consideration that we are required to follow as skilled clinicians.

This leads us to the final aspect of EBP…

The Role of Client Perspectives in Speech-Language Pathology

Client perspectives include the goals, values, and expectations of them (and their caregivers). Understanding client perspectives is important for many reasons. The ASHA Code of Ethics states that clinicians must “hold paramount the welfare of persons they serve professionally…” and understanding their perspectives is an important aspect of ensuring welfare. Recognizing and honoring client perspectives is also important for gaining client/caregiver buy-in to services and promoting the generalization of skills across natural contexts and settings.

One way to gain information about client perspectives is through ethnographic interviewing and utilizing questionnaires. Ethnographic interviewing aims to gain a deeper understanding of the client’s cultural background, beliefs, and practices related to communication. Questions asked in ethnographic interviews tend to be more open-ended to provide a wider breadth of information related to the client’s personal experiences, perspectives, and values. Questionnaires may be used in order to gain information about a client’s strengths and preferences.

Once you have analyzed your evidence, utilized your clinical expertise, AND gathered client perspectives, you are ready to make your informed decision!

No biggie, right? We wish. Effectively engaging in EBP can be challenging…but we have (a few) solutions.

Challenges (and Solutions) in Evidence-Based Practice

We recognize that there can be many barriers when engaging in EBP. Time can be the number one barrier; SLPs and other clinicians are often very busy and do not have extra time to search out external evidence resources for every single individual on their caseload (looking at you, SLPs with caseloads of 80+...). There are often paywalls on research articles as well. Additionally, clinicians and families may be resistant to change or to consider exploring a new approach.

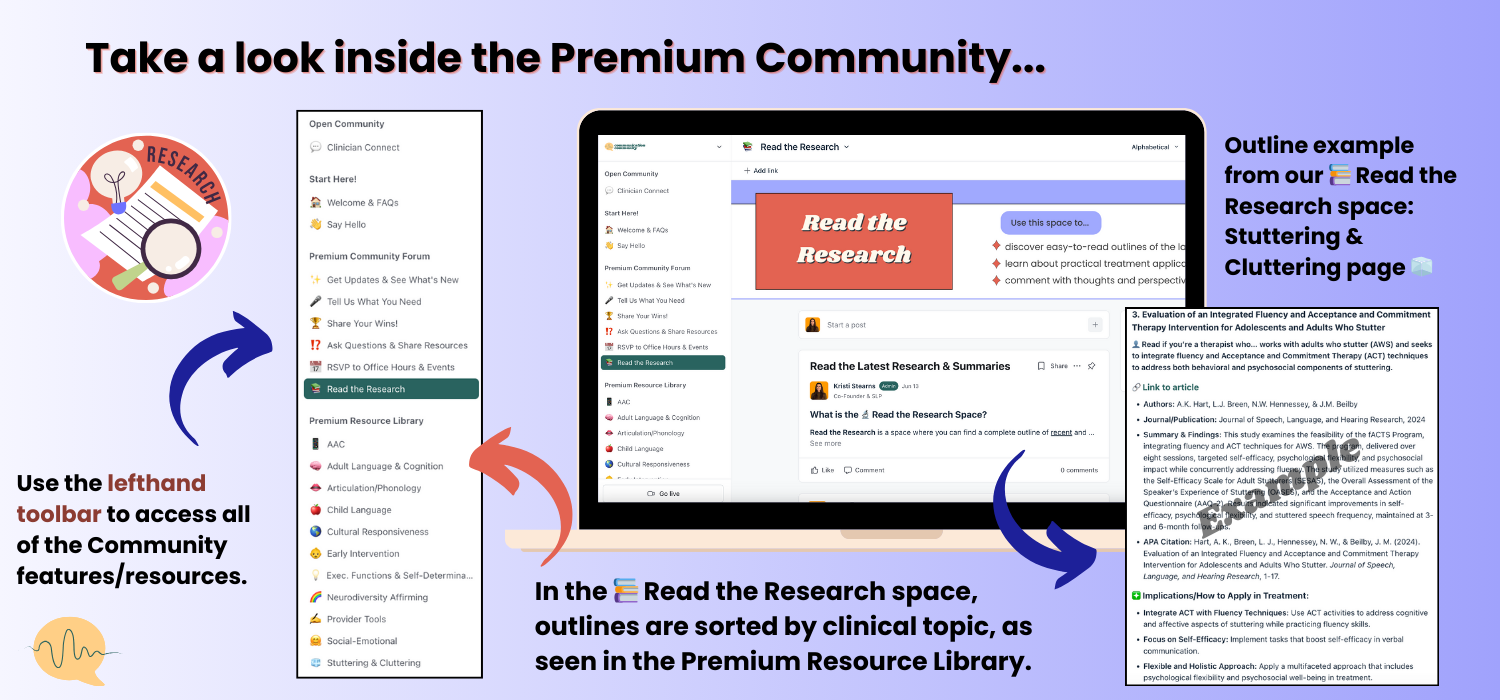

📚 Read the Research

Inside our Premium Community, where we offer unlimited downloads to our no-prep resources, we have a new space dedicated just to research.

Here, find up-to-date research summaries (and links to the full articles), which you can use to support your work! Read more about it, here.

Below, we have listed and linked resources for engaging in EBP, including ASHA Evidence Maps, which can eliminate some of the time constraints.

Unpaywall.org has an open database with millions of scholarly articles. You can add a browser extension, which shows you articles you can access as you search Google Scholar. This can eliminate some of the paywall difficulties.

It may take time to discuss change or new approaches with other clinicians, clients, and their support team. Change does not always happen overnight, but being persistent, and continuing to demonstrate the rationale behind a change, including citing evidence, can be an effective strategy.

Sources for Engaging in Evidence-Based Practice

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) provides a number of quality resources to promote engagement in EBP.

- An Overview of EBP and the process of EBP

- Step 1: Frame Your Clinical Question

- Step 2: Gather Evidence

- Step 3: Assess the Evidence

- Step 4: Make Your Clinical Decision

- Membership to ASHA provides access to many research articles, as well as Evidence Maps for many topics, ranging from apraxia to telepractice (and many many more).

- The Informed SLP team reads over 4000 articles a year and provides summaries and resources about new research.

More EBP Resources

In addition to the creation of our Read the Research space, we have created many resources covering a wide range of topics in speech and language assessment and therapy. As always, utilize your internal evidence, clinical expertise, and client perspectives when selecting resources 🙂. You can find all of them inside our Premium Membership Community.

References

Cooley Hidecker, M. J., Jones, R. S., Imig, D. R., & Villarruel, F. A. (2009). Using Family Paradigms to Improve Evidence-Based Practice. https://doi.org/10580360001800030212

Westby, C., Burda, A. N., & Mehta, Z. (2003). Asking the right questions in the right ways. The ASHA Leader, 8(8), 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.ftr3.08082003.4

![How to Write Apraxia Goals [with goal bank]](https://www.communicationcommunity.com/content/images/2025/07/Apraxia-Goals--2-.png)